(See also Julia Serano’s wonderful Transgender Glossary if you are interested in more. I link to it throughout.)

Gender “Identity”

Identity comes up regularly in trans politics, but refers to two very different concepts — often interchangeably, and without distinction.

-

Our conscious acts of identifying with a gender or sexuality — male, female, non-binary, fluid, straight, bi, gay, cis, trans, non-conforming, or otherwise. We all have multiple conscious identities, that intersect and change over time.

Those identities are curated, public, and often fluid. I’m still learning to identify as a woman, trans, and lesbian — even while the realities are more complex, queer, and fluctuating. I also identify as an author, a web developer, bi/pansexual, genderqueer, and polyamorous. None of this is unique to the trans experience.

-

Our vague and often-elusive sense of innate gender — something most people seem to have, but trans people spend more time dealing with. Subconscious sex is really a better term for understanding trans identities. This is not a conscious or curated self-labeling, but more like the sensation of being angry because you are hungry — a feeling that can be difficult to pin down. For some it is simply male or female, and becomes obvious early on — but for most of us it is more complex, and takes years to dig through the rubble of assumptions, fears, and prejudices around our bodies.

Cis people also have subconscious gender identities, though it’s more easy to assume that your sex is completely constructed or flows seamlessly from your genitalia when it has never been called into question.

“Biological” Sex

Many people distinguish “gender identity” (between the ears) from “biological sex” (between the legs) — as though one is natural and static, while the other is invented or fluid. That’s a vast oversimplification of the science, and a dangerous false dichotomy. Our identities don’t exist outside of biology, and sex is not fixed concept outside our identities. These two ideas are inseparable.

When a doctor assigns our gender at birth, they base the assignment on our genitalia alone. For the many people born with “ambiguous” genitalia, it’s common practice for doctors to perform surgery — assigning their “biological sex” by force. There were never two discrete categories to begin with.

When we try to talk about sex as a reproductive distinction, we’re really talking about internal gonads producing eggs or sperm: testis and ovary. Reproductive gonads often align with genitals, but not always, and not in any simple binary. Some people are infertile, some past menopause, or vasectomies, or other common reproductive changes — making it clear that gonads don’t directly correlate with what we call “biological” sex.

When we’re in public no one knows what genitals or gonads exist between our legs, but they feel comfortable assigning our sex anyway — based on the assumptions between their own ears. Social gendering relies mainly on “secondary sex characteristics” (especially masculine-associated facial hair etc) and gender presentation. Our lived sex — the way we are perceived and treated by others — has nothing to do with genitals or gonads.

Organizations like the International Olympic Committee have gone further, attempting to find a definable “biological sex” in chromosomes and hormone levels. The results are the same wherever you look: our biology is a complicated mix of genetic inclinations that interact with our experiences in complex ways over time.

Biology is fluid, identity is biological, and the male/female binary is more social than scientific.

“Transition”

Some trans people decide to change how we present to the world. We transition our public personas, hoping to bring our social lives and/or bodies more in line with our subconscious sex.

That means different things for different people, but “transition” is not a surgery, transgender is not a medical term, not all trans people transition, and we’re not all simply men or women in the wrong body moving from one binary to another. Transition is a million little things, for a million different reasons.

Some of us change our pronouns, or our names — either informally, or through legal channels. Some take hormones and/or hormone-blockers, a few get “top” surgeries to augment or remove breast tissue, and even fewer opt for genital surgery, tracheal shaves, and cosmetic interventions.

“After” transition (which has no real start or finish) we are the same person that we were before. With or without surgery, our genders are just as real. Transition does not complete us or make us “real” men and women. My body was already female, because I was. How and when and why we transition is more personal and complex than simple assimilation into cis society.

In October 2015, I decided to start a more intentional transition — first socially, and then medically. I don’t believe in a “true” self that was hidden before, or in vague concepts of authenticity, or finally becoming whole. I wasn’t born male, I was never a woman trapped in a man’s body, I’m not finally complete, I was never broken, and I will never be fixed.

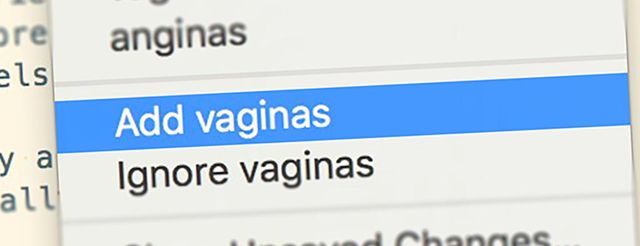

People regularly assume that my transition has or will soon involve genital surgery. Maybe. Maybe not. But transition was never about my genitals. Women are not vaginas, and men are not penises. I won’t finally be a woman if I have surgery, or let a man penetrate me. I’m not a new or different person, and there really was no chasm to cross over. My gender and orientation have not changed — only my social presentation and hormone levels.

I am not finally a woman, but you are finally aware of my womanhood.

“Passing”

Now that strangers correctly identify me as a woman, people say that I am “passing” as a woman. They’re wrong.

The language of passing is borrowed from racial politics (people of color passing as white) and later gay/lesbian politics (femme lesbians or butch gays passing as straight), where “passing” means your marginalized identity is not seen.

Passing is a complicated privilege — making it possible for marginalized people to avoid harassment and violence, at the cost of rejecting or hiding our marginal identities.

It’s also complicated because passing is done to us. In a single moment, different people will come to different conclusions about me, leaving me in a state of Schroedinger’s gender. My “passing” is based on other people’s assumptions about my history.

But passing language is particularly strange for trans people, who are said to be “passing” when we are identified correctly, in our appropriate genders. This plays into the popular notion that our gender is a costume we put on, and “passing” is the entire point of transition — the only way to be trans. People regularly try to help out by giving us unsolicited advice on our looks, voices, or movements — assuming that’s what we mean by transition.

There’s a history to that idea, enforced by the medical community since the 60’s when hormone replacement therapy started to become a medically-accepted treatment. Doctors established themselves as gender gatekeepers, determining who could transition medically — in part by enforcing strict binary stereotypes. Until recently, medical transition was only available if doctors thought you could “pass” well, and you promised to live straight and stealth after transition. The goal of “passing” was forced on us, and made trans communities invisible.

It might be more accurate to say that I “pass” as cis-gender at times, or that I previously learned to “pass” (well enough) as man. Trans people face a real and constant threat of violence, so blending in as cis can save our lives. It’s hard to constantly have your gender called into question, or made the center of conversation. Still, “passing” is not a goal we otherwise share.

Trans “Visibility”

In the last few years, everyone is talking about trans visibility. Chaz Bono danced with the stars, suddenly Lavern Cox is everywhere, Caitlin Jenner made transition a reality TV experience, and now you’re reading my blog.

New media comes out every year highlighting design trans characters — but most of them are written, directed, and acted by straight white men, reinforcing stereotypes more than reality. When a new show or movie comes out, we’re often more scared than excited.

These stories tend to focus on “men who think they are women” and love doing their makeup more than anything else. After transition they are either beautiful straight women who get the boy (making them finally “real” women), or pathetic creatures who need more help passing to be “successfully” trans.

Even the true stories are limited to rich and beautiful women who fit easily into our existing binary categories: men and women, just like you. Those stories are important, but they aren’t the whole picture. That’s not how we all do trans.

Where are the gender outlaws, the fluid identities, the femme boys and butch women who have always faced the brunt of harassment? Where are the trans people who are complex and confused, or happy to mix up our notions of gender? When we argue for bathroom rights based only on our ability to conform, we’re throwing our own community under the bus.

This narrow visibility has been a mixed bag for the trans community. More of us are coming out, and we’re doing it more publicly. For a minority that’s been forced into “stealth” invisibility, it’s wonderful to see (some of) us moving into the light. There’s power in numbers.

But the backlash has been swift and deadly — moving faster than our cultural gains. Trans women (and especially women of color) were already being killed at unprecedented rates — and those numbers are higher than ever. We’ve been using bathrooms since the invention of the toilet, but suddenly states are passing laws to mandate our bowel movements, or protect housing and job discrimination (a more basic concern for many trans people) as religious freedoms.

I was much more visibly queer a year ago. In some ways my transition has made me safer, by making me one more white woman on the street. All my femme interests or traits that used to make me queer now make me invisible. It’s easy for me to disappear into this over-simplified binary trans identity that doesn’t really reflect my experience. I want to be a proud gender-bending dyke, but that’s often used as proof that I’m really a man, not trans enough, or in need of gender-assimilating guidance.

Just because some of us are in the spotlight doesn’t mean we’re all being seen.

Just Like (Not) You

Across the board, marginalized groups face a complex problem often referred to as respectability politics. The quickest way into the mainstream is conformity — but what are the costs, and who is left behind? Many rights-movements have devolved into “just like you” or “born this way” rhetoric, allowing those of us who “pass” in the mainstream to go about our lives as long as we’re willing to blend in.

For a few of us, that’s great — or at least good enough — but it’s not the whole story, and it’s not the end of our movement. I don’t want to get married, and use gendered toilets like any “normal” cis straight person — I actually want these systems to break down, and conform better to us. No matter how well my looks or identity fit the popular trans mythology, I want to fight for something more fluid and open, that helps the whole world be more queer.

I am a woman, and I am not just like all cis women. I will continue to fight both sides of that argument, until all my friends have the right to live all our identities in the ways we see fit: monogamous or polyamorous; straight or bi, pan or gay; sex workers, sluts, and prudes; trans-binary, gender-fluid, butch and femme; black, brown, immigrant, Muslim, and interracial; asexual, intersex, closeted, and queer.

We can’t keep accepting identities one-at-a-time, based on their ability to assimilate with established (straight white cis) norms. We have to rebuild these systems with new, more fluid and queer assumptions.